Brickopolis: under Manchester

- Paul Dobraszczyk

- Jan 30, 2011

- 2 min read

Manchester walks offer an occasional tour titled ‘Underground Manchester’. From my past experiences in London, these tours promise much in their titles but usually deliver very little as regard actual subterranean space, so beset are official tours with stringent safety regulations. At its start, this Manchester tour seemed to fit the pattern: a long ramble through the city streets, with the guide talking about Manchester’s underground, now sealed off and inaccessible. However, half way through the tour, things took a dramatic turn as the party of 35 mainly elderly visitors descended an 80-ft staircase beneath the Great Northern entertainment complex, an ultra-modern, ultra-bland building housed inside what was previously the gargantuan Great Northern warehouse – a Victorian building that stored industrial quantities of cotton in the Victorian period.

The entrance chamber in the former canal

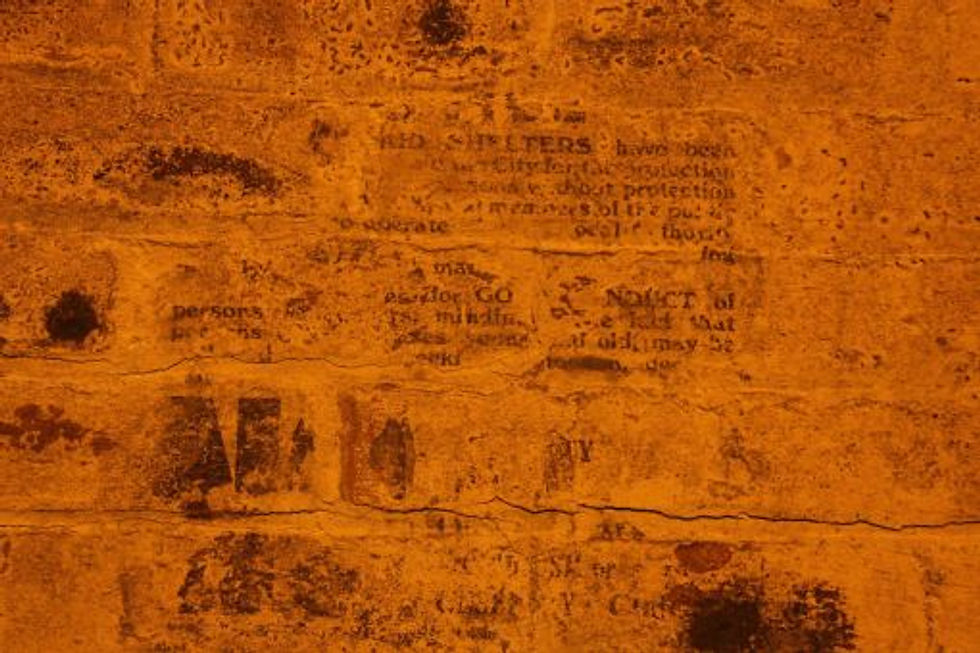

At the bottom of the stairs, we entered the former Manchester and Salford Junction Canal, built in 1829 underneath the city centre from the Rochdale Canal to the River Irwell to transport goods between the Great Northern Railway Warehouse on Deansgate to Grape Street, near to what is now Granada Studios. The 17-ft high tunnel of the former canal still visibly sweats and drips, fogging my camera lens immediately and making photography difficult. Sparsely lit, this space was where thousands of Mancunians would have entered during the Blitz to escape the German bombs that fell on the city from 1940-41. Inscribed on the wall are the remains of the official instructions to these reluctant troglodytes – rules as to how to behave in this most unusual of environments.

Faded instructions to wartime shelterers

In fact, this space is but a portal into an extraordinary subterranean world, completely unlit, slippery underfoot, and filled with rubble. That the group was allowed to enter these spaces was remarkable enough, and they felt every bit as wild and alien as other underground spaces shut off from public view. With almost hostile indifference to my top-of-the-range camera, the cavernous spaces appeared and reappeared in fantastical moments of sublime architecture, such as a great brick arch spanning one of the caverns with an almost impudent sense of the outlandish.

The brick cavern

What these spaces are testament to is the fundamentally subterranean quality of the modern industrial city. For Manchester was quite literally hollowed out and refashioned by the quintessential Victorian material – brick – manufactured in such quantities as to remake the very earth itself into a space that Piranesi could but dream of. The vastness and inhuman quality of these brick spaces does not fit with their conversion to shelters for anxious wartime residents (in contrast to the rather more homely chalk tunnels of the Chislehurst caves in London, also used to shelter thousands during the Blitz). In fact, one anonymous artist – perhaps one of the unfortunate wartime shelterers – has scrawled an image of the devil on one of the walls, as if representing the being most well-suited to live in this nightmarish world. If the Victorians modernised cities like Manchester by remaking its subterranean spaces, they also created, through those very spaces, a world that seemed reminiscent of something far more ancient.

The devil's own realm

Hôm trước mình có lướt mạng và thấy có nhiều người đề cập đến bongdaso trong khi bàn về kết quả các trận bóng, nên cũng tò mò mở ra xem thử. Mình chỉ xem qua trong một thời gian ngắn để nắm bắt cách sắp xếp thông tin, tỷ số và các mục khác. Cảm giác là giao diện rất dễ nhìn, từng phần được phân chia rõ ràng, vì vậy đọc lướt cũng không thấy rối mắt. Theo mình, như vậy là đủ để cập nhật thông tin cơ bản rồi trên bongdaso.org.

I had no idea about the fascinating underground history of Manchester! Reminds me of exploring hidden spots while playing Drift Boss. It's all about finding those gems beneath the surface!