Mills: a Manchester metonym

- Paul Dobraszczyk

- Oct 3, 2017

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 12, 2020

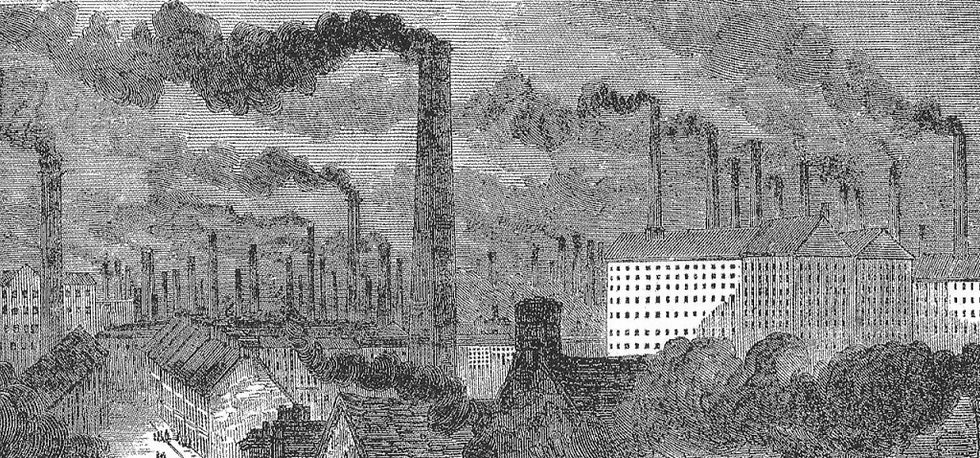

‘Manchester, getting up the steam’, The Builder, October 1853.

In October 1853, the British architectural journal The Builder pictured Manchester ‘getting up the steam’, an image of the city’s forest of tall smoking chimneys, interspersed with large unadorned cotton mills, with their repetitive rows of identical windows, and diminutive groups of terraced houses. This engraving still sums up what for many is the dominant image of Manchester’s Victorian and more recent history as Cottonopolis: a soot-filled city of polluting industry, damp and unrelenting monotony. Within this imagined Manchester, epitomized by the paintings of L. S. Lowry, cotton mills tower over all other buildings, dominating the visual appearance of the cityscape. Today, in some parts of the Greater Manchester region, such as parts of Bolton, Oldham, and Stockport, mill buildings still dominate in this way, even if their chimneys have long since ceased belching smoke.

L. S. Lowry, The Pond, 1950

Devon Mill (1908) in the Hollinwood district of Oldham

From the late eighteenth-century onwards, over 2,400 cotton mills and cloth-finishing works were built in what would in 1974 become the Greater Manchester region: a territory approximately 25 miles north to south and 30 miles east to west. In their exhaustive survey of these structures, which was begun in 1985, David Farnie and Mike Williams found that less than half (1,112) of these factories had survived, with many either derelict or awaiting grant-aided demolition. Since then, many more mills have been lost: the sheer number and vast size of these structures make them particularly difficult to convert to non-industrial uses.

William Wyld, Manchester from Kersal Moor, 1852

Despite many losses through demolition, Manchester’s mills have long featured in postwar images of the city as a landscape of lingering dereliction and decay. As the German emigré Max Ferber recalled in W. G. Sebald’s novel The Emigrants (1993), his arrival in Manchester in 1942 summoned up the memory of thousands of smoking chimneys that he saw on viewing the city from the surrounding hills. Yet, by the mid-1960s, when Sebald met Frank Auerbach, the artist who had inspired the fictional Ferber, ‘almost every one of those chimneys [had] now been demolished or taken out of use.’ However, the remnants of this landscape of mills continued to persist in the city in the 1960s, as evidenced in a scene filmed in Oldham in the film Hell Is A City (Val Guest, 1960), where the town’s half-ruined millscape is revealed panoramically when a group of illegal gamblers flee from a police raid on a moor on Oldham Edge; or in a more sustained way in A Taste of Honey (Tony Richardson, 1961), where the Victorian mills of Ancoats, Stockport and Miles Platting dominate the still-industrial landscape that frames the poignant story of young social outcasts in a bleak, half-ruined city.

Still from Hell is a City (1960) showing the mills of Oldham in the background

Still from A Taste of Honey (1961) showing Victoria Mill from the Rochdale Canal, Miles Platting

Victoria Mill today

In the 1960s and 1970s, the city and region’s mills continued to slide towards redundancy, with textile production in almost all of these buildings ceasing by the early 1980s. Whilst the move towards regeneration in the 1990s saved some of the more iconic mill structures, particularly those like Royal Mills and Murrays’ Mills in Ancoats that were listed or located near to the city centre, many others fell into disrepair, either being partially reused or succumbing to dereliction and decay. Some, like Brunswick Mill (c.1840) in Ancoats, survive in a state of suspended animation: part of this mill, once the largest in the city, houses a small-scale textile businesses and cheap practice spaces for musicians; the rest is boarded up – a bleak and forbidding wall of decaying brick as seen from the adjacent Ashton Canal.

Royal Mills (centre-left) and Murrays’ Mills (centre-right), Ancoats, as seen from the canal basin in New Islington

Brunswick Mill (c.1840) from Pollard St, Ancoats

Hartford Mill (1907) in Werneth, Oldham, currently awaiting demolition

Surviving cotton mills, whatever their state of disrepair, present opportunities for reflection on the memories of industry itself. These memories are highly valued by many in relation to Greater Manchester’s existing cotton mills, including a few textile companies that continue to use and care for these buildings, for example Kearsley Mill (1905-06) in Prestolee that is still occupied and well-maintained by its original owner, Richard Haworth Ltd. Local conservation groups, such as the Ancoats Buildings Preservation Trust, campaign to preserve historic mills, while the National Trust owns Quarry Bank Mill (1784) to the south of Manchester and the site’s many volunteers dramatically re-enact its social history for visitors. Finally, arts events like Angel Meadow, the audience-immersive theatre production held in Ancoats in June 2014, provide insights into the lives of former textile-workers (in the case of Angel Meadow, Irish immigrants who dominated the area in the nineteenth century).

Kearsley Mill (1905-6) in Prestolee

The National Trust-owned Quarry Bank Mill in Cheshire, built in 1784

The engine-house of Pear Mill (1907-12) in Bredbury, Stockport, now used as an indoor climbing centre

Finally, if many of Greater Manchester’s mills have either been demolished or fallen into a state of ruin, others have found alternative uses, including, in addition to heritage sites like Quarry Bank Mill: children’s and adult’s play areas (for example Run of the Mill and a climbing centre, both located in Pear Mill in Stockport); self-storage or warehousing facilities (Chadderton Mill, Oldham); nightclubs (Downtex Mill); apartments (Royal Mills); and even public sector services (a health and education centre in Victoria Mill, Miles Platting). These conversions offer insights into how otherwise defunct industrial buildings might be salvaged and reused and also how their historical development might be remembered. Manchester’s mill buildings still offer an afterimage of ‘mythic’ Manchester, the city defined by writers such as Thomas Carlyle, Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell, in which the cotton mill represented not only a certain type of work but the entire industrial system. These mills may no longer act as a metonym of Manchester as Cottonopolis; but they nevertheless continue to hold out the possibility of integrating the city’s industrial history with its present and future development as both remainders and reminders of what has passed.

This post is adapted from my book The Dead City: Urban Ruins and the Spectacle of Decay (IB Tauris, 2017), available to buy as a reasonably-priced Kindle version here.

#HartfordMill #HellisaCity #painting #VictoriaMill #ATasteofHoney #LSLowry #PearMill #MilesPlatting #QuarryBankMill #WilliamWyld #TheBuilder #ruins #industry #Cottonopolis #regeneration #Manchester #mills #BrunswickMill #DevonMill #Chadderton #Ancoats #Bolton #Stockport #salvage #restoration #Prestolee #Victorian #KearsleyMill #fiction #Oldham #cotton #RoyalMills #film

Comments